Trauma

This was previously featured in an exam

A 34 year old man is brought to ED with a stab wound through the left hand side of his back. On examination, there is weakness of the left side of the body and loss of pain sensation on the right side of the body. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Answer:

This is the classical Brown-Sequard syndrome caused by hemisection of the spinal cord. There is ipsilateral motor loss (corticospinal tract) and loss of fine-touch/vibration/proprioception sensation (posterior column) with contralateral loss of pain/temperature sensation (spinothalamic tract) due to decussation of the spinothalamic tract fibres within the spinal cord.Spinal Trauma: Spinal Cord Injury

Trauma

Last Updated: 14th December 2023

The spinal cord originates at the caudal end of the medulla oblongata at the foramen magnum. In adults, it usually ends near the L1 bony level as the conus medullaris. Below this level is the cauda equina, which is somewhat more resilient to injury.

Spinal cord tracts

Of the many tracts in the spinal cord, only three can be readily assessed clinically: the lateral corticospinal tract, spinothalamic tract, and dorsal columns. Each is a paired tract that can be injured on one or both sides of the cord. When a patient has no demonstrable sensory or motor function below a certain level, he or she is said to have a complete spinal cord injury. An incomplete spinal cord injury is one in which some degree of motor or sensory function remains; in this case, the prognosis for recovery is significantly better than that for complete spinal cord injury.

| Tract | Location | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Dorsal columns | Posteromedial aspect of cord | Transmits ipsilateral proprioception, vibration and fine-touch sensation |

| Spinothalamic tract | Anterolateral aspect of cord | Transmits contralateral pain, crude-touch and temperature sensation |

| Lateral corticospinal tract | Posterolateral aspect of cord | Controls ipsilateral motor power |

![By Polarlys and Mikael Häggström [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://mrcemsuccess.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Cross-sectional-cord.png)

Spinal cord tracts. (Image by Polarlys and Mikael Häggström [CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons)

Spinal cord injuries

Spinal cord injuries can be classified according to level, severity of neurological deficit, spinal cord syndromes, and morphology.

- Level of spinal cord injury

- The bony level of injury refers to the specific vertebral level at which bony damage has occurred. The neurological level of injury describes the most caudal segment of the spinal cord that has normal sensory and motor function on both sides of the body. The neurological level of injury is determined primarily by clinical examination.

- The term sensory level is used when referring to the most caudal segment of the spinal cord with normal sensory function. The motor level is defined similarly with respect to motor function as the lowest key muscle that has a muscle-strength grade of at least 3 on a 6-point scale. The zone of partial preservation is the area just below the injury level where some impaired sensory and/or motor function is found.

- Frequently, there is a discrepancy between the bony and neurological levels of injury because the spinal nerves enter the spinal canal through the foramina and ascend or descend inside the spinal canal before actually entering the spinal cord. Determining the level of injury on both sides is important.

- Severity of neurological deficit

- Spinal cord injury can be categorised as:

- Incomplete or complete paraplegia (thoracic injury)

- Incomplete or complete quadriplegia/ tetraplegia (cervical injury)

- Any motor or sensory function below the injury level constitutes an incomplete injury and should be documented appropriately. Signs of an incomplete injury include any sensation (including position sense) or voluntary movement in the lower extremities, sacral sparing, voluntary anal sphincter contraction, and voluntary toe flexion.

- Spinal cord injury can be categorised as:

- Morphology of spinal injury

- Spinal injuries can be described as fractures, fracture dislocations, spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormalities (SCIWORA), and penetrating injuries. Each of these categories can be further described as stable or unstable.

- However, determining the stability of a particular type of injury is not always simple and, indeed, even experts may disagree. Particularly during the initial treatment, all patients with radiographic evidence of injury and all those with neurological deficits should be considered to have an unstable spinal injury. Spinal motion of these patients should be restricted, and turning and/or repositioning requires adequate personnel using logrolling technique until consultation with a specialist, typically a neurosurgeon or orthopaedic surgeon.

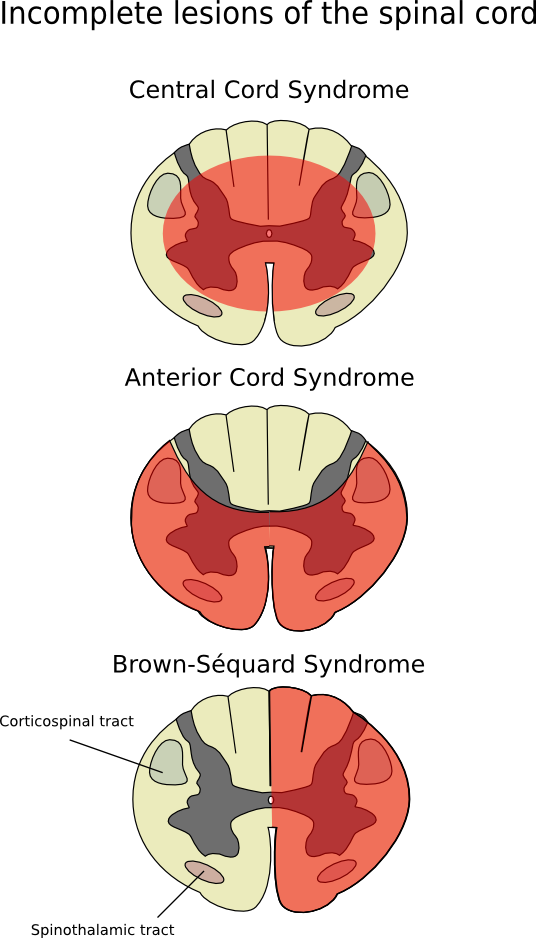

- Spinal cord syndromes

- Characteristic patterns of neurological injury are encountered in patients with spinal cord injuries, such as central cord syndrome, anterior cord syndrome, and Brown-Séquard syndrome. It is helpful to recognise these patterns, as their prognoses differ from complete and incomplete spinal cord injuries.

Comparison of spinal cord syndromes

| Spinal cord syndrome | Mechanism | Tracts affected | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete cord transection | Major trauma | All tracts |

|

| Brown-Séquard syndrome | Hemitransection e.g. penetrating trauma or unilateral compression of the cord | All tracts on one side |

|

| Central cord syndrome | Hyperextension injury of cervical spine in patient with pre-existing cervical stenosis e.g. forward fall with facial impact in elderly patient (can occur even without cervical spine fracture/dislocation) | Corticospinal tract and spinothalamic tract |

|

| Anterior cord syndrome | Occlusion of anterior spinal artery with infarction of anterior cord by direct anterior cord compression, flexion injuries of the cervical spine, or thrombosis of anterior spinal artery | Corticospinal, spinothalamic and spinocerebellar tracts |

|

| Posterior cord syndrome | Penetrating trauma to the back or hyperextension injury associated with vertebral arch fractures (very rarely occurs in isolation) | Dorsal column |

|

Incomplete Lesions of Spinal Cord. (Image by Fpjacquot, via Wikimedia Commons)

Neurogenic vs spinal shock

- Neurogenic shock

- Neurogenic shock results in the loss of vasomotor tone and sympathetic innervation to the heart.

- Injury to the cervical or upper thoracic spinal cord (T6 and above) can cause impairment of the descending sympathetic pathways. The resultant loss of vasomotor tone causes vasodilation of visceral and peripheral blood vessels, pooling of blood, and, consequently, hypotension. Loss of sympathetic innervation to the heart can cause bradycardia or at least the inability to mount a tachycardic response to hypovolaemia.

- When shock is present, it is still necessary to rule out other sources because hypovolaemic (haemorrhagic) shock is the most common type of shock in trauma patients and can be present in addition to neurogenic shock.

- The physiologic effects of neurogenic shock are not reversed with fluid resuscitation alone, and massive resuscitation can result in fluid overload and/ or pulmonary oedema.

- Judicious use of vasopressors may be required after moderate volume replacement, and atropine may be used to counteract haemodynamically significant bradycardia.

- Spinal shock

- Spinal shock refers to the flaccidity (loss of muscle tone) and loss of reflexes that occur immediately after spinal cord injury. After a period of time, spasticity ensues.

Effect of spinal cord injury on other organs

- When a patient’s spine is injured, the primary concern should be potential respiratory failure. Hypoventilation can occur from paralysis of the intercostal muscles (i.e. injury to the lower cervical or upper thoracic spinal cord) or the diaphragm (i.e. injury to C3 to C5).

- The inability to perceive pain can mask a potentially serious injury elsewhere in the body, such as the usual signs of acute abdominal or pelvic pain associated with pelvic fracture.

Report A Problem

Is there something wrong with this question? Let us know and we’ll fix it as soon as possible.

Loading Form...

- Biochemistry

- Blood Gases

- Haematology

| Biochemistry | Normal Value |

|---|---|

| Sodium | 135 – 145 mmol/l |

| Potassium | 3.0 – 4.5 mmol/l |

| Urea | 2.5 – 7.5 mmol/l |

| Glucose | 3.5 – 5.0 mmol/l |

| Creatinine | 35 – 135 μmol/l |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) | 5 – 35 U/l |

| Gamma-glutamyl Transferase (GGT) | < 65 U/l |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) | 30 – 135 U/l |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST) | < 40 U/l |

| Total Protein | 60 – 80 g/l |

| Albumin | 35 – 50 g/l |

| Globulin | 2.4 – 3.5 g/dl |

| Amylase | < 70 U/l |

| Total Bilirubin | 3 – 17 μmol/l |

| Calcium | 2.1 – 2.5 mmol/l |

| Chloride | 95 – 105 mmol/l |

| Phosphate | 0.8 – 1.4 mmol/l |

| Haematology | Normal Value |

|---|---|

| Haemoglobin | 11.5 – 16.6 g/dl |

| White Blood Cells | 4.0 – 11.0 x 109/l |

| Platelets | 150 – 450 x 109/l |

| MCV | 80 – 96 fl |

| MCHC | 32 – 36 g/dl |

| Neutrophils | 2.0 – 7.5 x 109/l |

| Lymphocytes | 1.5 – 4.0 x 109/l |

| Monocytes | 0.3 – 1.0 x 109/l |

| Eosinophils | 0.1 – 0.5 x 109/l |

| Basophils | < 0.2 x 109/l |

| Reticulocytes | < 2% |

| Haematocrit | 0.35 – 0.49 |

| Red Cell Distribution Width | 11 – 15% |

| Blood Gases | Normal Value |

|---|---|

| pH | 7.35 – 7.45 |

| pO2 | 11 – 14 kPa |

| pCO2 | 4.5 – 6.0 kPa |

| Base Excess | -2 – +2 mmol/l |

| Bicarbonate | 24 – 30 mmol/l |

| Lactate | < 2 mmol/l |